Summary: Hunter-gatherer kids in the Congo Basin learn vital skills like hunting, gathering, and care by time six or seven, thanks to a unique cultural learning atmosphere. Unlike Western societies, where teaching is generally parent- or teacher-centered, these children get understanding from parents, peers, extended family, and related adults within their small, democratic communities. This extensive networking promotes the development of skills across generations through a process known as combined culture.

Important Information:

- Hunter-gatherer children get quarter of their historical information from non-relatives.

- Smaller, close living surroundings promote observation-based learning from different sources.

- Democratic values and independence encourage self-driven, non-coercive ability exploration.

Origin: Washington State University

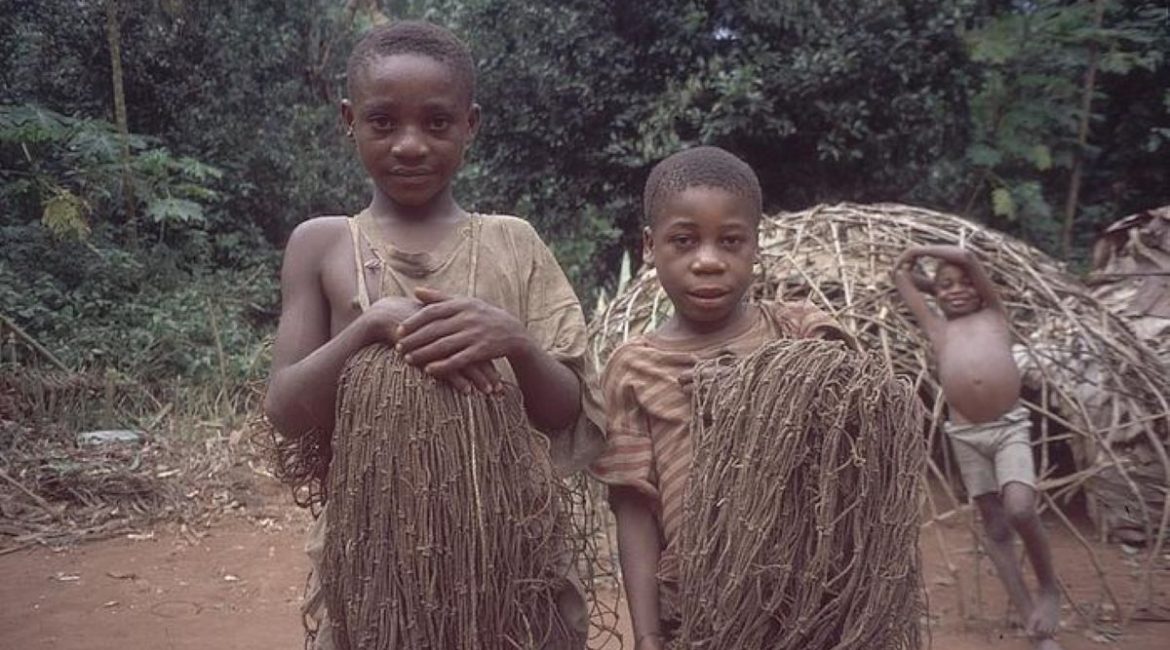

Hunter-gatherer kids in the Congo Basin are frequently taught how to kill, identify edible flowers, and care for children by the age of six or seven, in contrast to kids in the United States.

According to a new study conducted by Washington State University for the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, this quick learning is made possible by a special cultural setting where social information is passed down from both parents and the wider society.

The study explains how numerous historical characteristics have survived in hunter-gatherer communities across a variety of African natural settings for thousands of years.

” We focus on hunter-gatherers because this way of life characterized 99 % of human history”, said Barry Hewlett, a professor of anthropology at WSU and lead author of the study.

” Our bodies and minds are adapted to this close, little party life, rather than to modern industrial life. We want to find out the methods that have enabled people to adapt to various global surroundings by studying how kids in these societies learn.

For the review, Hewlett and colleagues use observing and historical data to analyze nine different modes of social transmission, meaning from whom and how children learn, in hunter-gatherer societies.

According to their analysis, extended family members are more likely to have contributed to the transmission of knowledge among children than previously thought.

Additionally, according to the study, about half of the cultural knowledge that children and adolescents hunt for and learn from are unrelated. This contrasts with earlier studies on the subject that focused more on the transfer of knowledge between parents and children.

According to Hewlett, the findings are likely to be attributable to a wide range of sources, including parents, peers, and even unrelated adults in the community, including unrelated adults. This contrasts with the Western nuclear family model, which emphasizes either the education of students through formal education.

In hunter-gatherer societies, intimate living conditions contribute to the broad, informal learning network. Small camps provide a space for children to observe and interact with a wide range of people, typically consisting of 25 to 35 people living in homes that are a few feet apart.

Through a method that is frequently subtle and nonverbal, they can learn important skills, such as cooking, hunting, and gathering, as well as caring for children.

Additionally, the study emphasizes the value of egalitarianism, respect for individual autonomy, and significant sharing in shaping how hunter-gathererers are taught to inherit cultural knowledge. Children, for instance, are taught the value of equality and autonomy by observing both their own behavior and that of others.

They are given the freedom to experiment and practice skills independently, fostering a thorough understanding of their culture, despite being not required to do so.

Hewlett said,” This way of learning contributes to what we call” cumulative culture,” or” building on existing knowledge and passing it down through generations.”

Humans have developed complex mental and social structures that allow for the transmission of thousands of cultural traits, unlike in many non-human animals, where social learning is restricted to a few skills. This has enabled us to innovate and adapt to various environments, from dense forests to arid deserts”.

Hewlett hopes that this study will provide a more in-depth understanding of how cultures in general are preserved and altered over time as well as the nature of social learning in people.

His coauthors on the study are Adam Boyette, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Sheina Lew-Levy, Durham University Department of Anthropology, Sandrine Gallois, Autonomous University of Barcelona Institute of Environmental Science and Technology, and Samuel Dira, Hawassa University Department of Anthropology.

About this news from research into learning and neurodevelopment

Author: Will Ferguson

Source: Washington State University

Contact: Will Ferguson – Washington State University

Image: The image is credited to WSU

Original Research: Open access.

” Cultural transmission among hunter-gatherers” by Barry Hewlett et al. PNAS

Abstract

Cultural transmission among hunter-gatherers

We examine from whom children learn in mobile hunter-gatherers, a way of life that characterized much of human history.

Recent studies on the modes of transmission in hunter-gatherers are reviewed before presenting an analysis of five modes of transmission described by Cavalli-Sforza and Feldman]L. L. Cavalli-Sforza, M. W. Feldman, Cultural Transmission and Evolution: A Quantitative Approach ( 1981 ) ] but not previously evaluated in hunter-gatherer research.

We also present two modes of group transmission, conformist transmission, and concerted transmission, seldom mentioned in hunter-gatherer social learning research, and propose a unique mode of group transmission called cumulative transmission.

Because previous studies have largely failed to distinguish between intrafamilial and extrafamilial transmission, the additional transmission modes, and their significance on cultural evolutionary signatures like the preservation of cultural traits, have been underestimated.

However, field data also points out that hunter-gatherer children interact with and learn from a large number of nongenetically related people, and that about half of children’s and adolescents ‘ horizontal and oblique social learning originated from nongenetically related people.

At least three different types of group transmission are possible thanks to the intimate living conditions of hunter-gatherers.

Theoretically, all three groups ‘ transmission contribute to the preservation of culture, homogeneity of intracultural diversity, and high intercultural diversity.

The various ways that hunter-gatherer children learn, how cultures are preserved, and how collective culture is shaped by discussion of previous and unique modes of group transmission as well as by analysis of additional oblique and horizontal transmission modes.