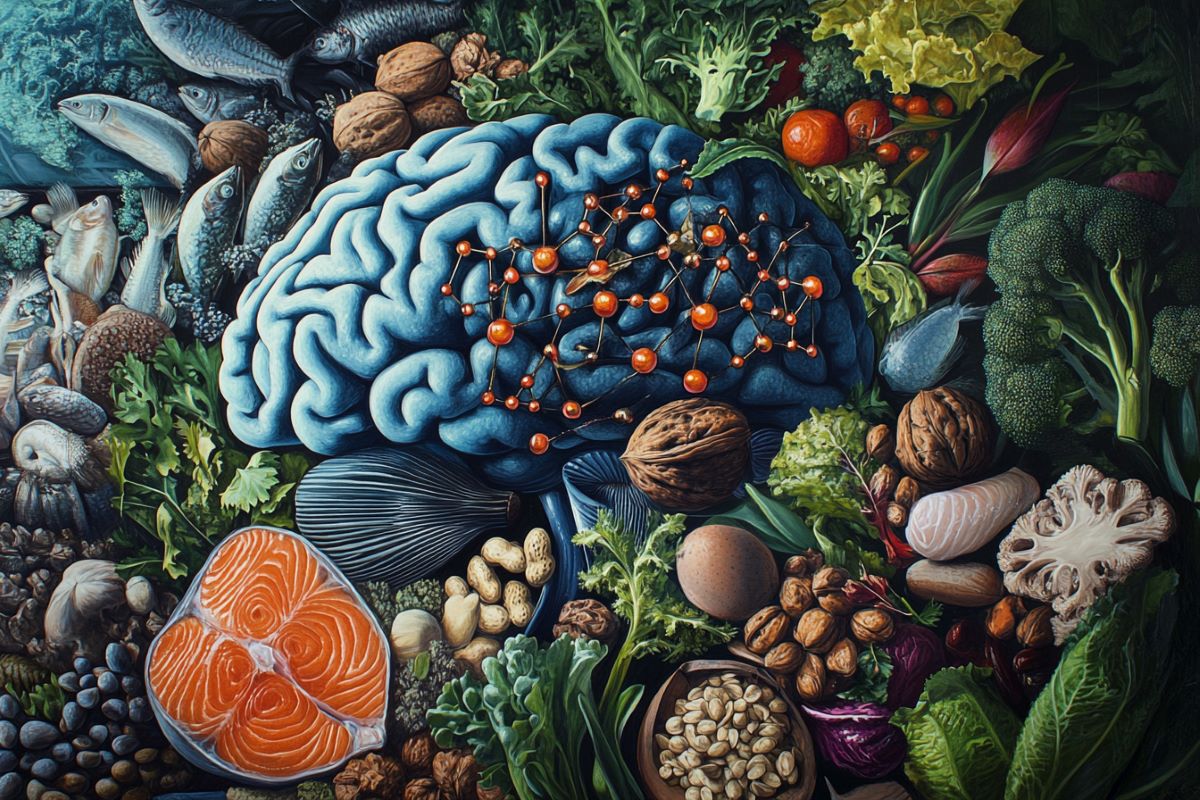

Summary: New research suggests that some vitamins may help to reduce brain metal formation, a factor that is linked to aging mental drop. Over a certain amount of non-heme copper, which accumulates over time, causes oxidative stress and can affect professional function and memory.

Over three decades, participants with higher consumption of antioxidants, vitamins, and iron-chelating nutrients showed less mental metal concentration and better mental efficiency. These findings highlight the benefits of Mediterranean or DASH nutrition in promoting brain health and preventing cognitive decline as people age.

Important Information:

- Iron’s Role: Excess head iron, particularly non-heme metal, is linked to poor storage and administrative work in aging.

- Nutritional Impact: Higher consumption of antioxidants, vitamins, and iron-chelating nutrition reduces mental metal formation.

- Dietary Potential: Food rich in these vitamins, such as the Mediterranean or DASH food, does protect against mental decline.

Origin: University of Kentucky

Researchers at the University of Kentucky discovered that embracing particular nutrients into a normal diet does lower iron formation in the brain, a risk factor for mental decline in normal aging.

The research,  , titled” Exploring the links among mental metal concentration, mental performance, and nutritional intake in older adults: A horizontal MRI study”, was published in , Neurobiology of Aging.

The job was supported by many offers from the National Institutes of Health ‘s , National Institute on Aging , and , National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

According to Brian Gold, Ph. D.,” It’s crucial to understand how nutrition and other lifestyle factors affect the risk of Alzheimer’s and related illnesses as we get older.” D., professor in the Department of Neuroscience in the , College of Medicine, university in the , Sanders-Brown Center on Aging , and main investigator of the investigation.

This study serves as an example of how we can promote healthier life choices to overcome some risk factors that may impact brain health, Gold said.

In this task, researchers particularly looked at non-heme metal, which is crucial for brain health. This kind of iron does not bind to storage proteins, which you, with age and in excess, cause oxidative stress, which could have an impact on synaptic integrity and cognition.

Abnormal brain metal has been linked to poor mental performance, even in normal ageing.

There are no established methods for reducing mental metal formation in older people, according to Valentinos Zachariou, Ph. D.,” Despite mounting evidence linking iron overload to bad cognitive result.” D., the primary author of the paper and assistant teacher in the College of Behavioral Science’s Department of Behavioral Science.

This study builds on the research team ‘s , previous work , that found that higher consumption of polyphenols, vitamins, iron-chelating nutrition and polyunsaturated fatty acid correlated with lower mental iron levels and better working memory efficiency.

” We still had important questions that remained unanswered in that initial investigation, particularly regarding the long-term effectiveness of these nutrients and their potential to reduce age-related brain iron accumulation”, said Zachariou.

For a follow-up study, Gold and Zachariou worked with the same research team, including the Department of Neuroscience’s Colleen Papas, Ph. D., Christopher Bauer, Ph. D., and Elayna Seago.

The study looked at the same cohort of older adults ‘ brain iron levels about three years later. They used a particular MRI technique known as quantitative susceptibility mapping to measure brain iron levels.

Researchers also analyzed a month’s worth of dietary information and cognitive performance, which were analyzed using neuropsychological tests of executive function and episodic memory.

According to Zachariou, “our findings revealed a large network of cortical and subcortical brain regions where iron accumulation occurred over a three-year period.”

At the follow-up time point,” these regional increases in iron levels were related to poorer episodic memory and executive function.”

” However, participants who had higher baseline intake of antioxidants, vitamins, iron-chelating nutrients, and polyunsaturated fatty acids showed significantly less iron accumulation over the three-year period”, said Gold.

The research team claimed that the findings provide important information for upcoming clinical trials to examine the effects of consuming comparable amounts of food on brain iron levels and cognitive function.

Further research on the benefits of healthy diets rich in the nutrients studied in this study, such as the Mediterranean or DASH diets, would be very helpful.

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the , National Institute on Aging , of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers , R01AG055449, R01AG068055, P30AG072946 and P30AG028383, by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number RF1NS122028, and the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number , S10OD023573.

The authors are solely responsible for the content, which does not necessarily reflect the official opinions of the National Institutes of Health.

About this information about research into diet and brain health

Author: Lindsay Travis

Source: University of Kentucky

Contact: Lindsay Travis – University of Kentucky

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

” Exploring the links among brain iron accumulation, cognitive performance, and dietary intake in older adults: A longitudinal MRI study” by Brian Gold et al. Neurobiology of Aging

Abstract

Exploring the links among brain iron accumulation, cognitive performance, and dietary intake in older adults: A longitudinal MRI study

This study looked at the role of specific nutrients in mitigating iron accumulation in older adults ‘ longitudinal brain iron accumulation, cognition, and cognition.

MRI-based, quantitative susceptibility mapping estimates of brain iron concentration were acquired from seventy-two healthy older adults ( 47 women, ages 60–86 ) at a baseline timepoint ( TP1 ) and a follow-up timepoint ( TP2 ) 2.5–3.0 years later.

Dietary intake was evaluated at baseline using a validated questionnaire. Using the same data set ( Version 3 ) neuropsychological tests for episodic memory ( MEM) and executive function ( EF), cognitive performance was evaluated at TP2.

Voxel-wise, linear mixed-effects models, adjusted for longitudinal gray matter volume alterations, age, and several non-dietary lifestyle factors revealed brain iron accumulation in multiple subcortical and cortical brain regions, which was negatively associated with both MEM and EF performance at T2.

However, consumption of specific dietary nutrients at TP1 was associated with reduced brain iron accumulation.

Our study provides a map of the brain regions that older adults have accumulated iron in over a short 2.5-year follow-up, and suggests that some dietary supplements may slow down brain iron accumulation.