Summary: Researchers have found that ketamine’s antidepressant results specific astroglia, a type of mental support body, rather than cells, challenging regular views. Using fish, scientists observed that morphine suppressed the “giving up” habits caused by folly signals, an impact linked to astroglial stimulation.

Whole-brain scanning revealed morphine overstimulated astrocytes, reducing their sensitivity to stress indicators and making the fish more frequent. Similar systems have been demonstrated in mice, which suggests that astroglia play a vital role in treating depression.

Important Facts:

- Astroglia Role: Ketamine activates astroglia, reducing their responsiveness to pressure signs.

- Cross-Species Information: Astroglia’s response to morphine was confirmed in both fish and animals.

- New Targets: The research suggests targeting astroglia could lead to tale depression treatments.

Origin: HHMI

Ketone, a decades-old analgesic, may revolutionize the treatment of severe depression, but some people still have questions about how the drug works, including how the brain’s cells and circuits are affected.

To support answer these concerns, researchers are turning to an improbable animal: small, days-old fish.

The millimeter-long, shiny zebrafish exhibits a “giving up” conduct, which scientists use to research depression in animals. It may not go as deep as humans do, but the fish do.

By taking advantage of this behavior, the ability to image the zebrafish’s whole brain, and a special virtual reality system, a team of researchers from HHMI ‘s , Janelia Research Campus, Harvard, and Johns Hopkins found where ketamine works in the fish mind: at supporting tissues called astroglia, more than cells.

According to past research conducted by Janelia scientists, astroglia serve as a countermeasure for the fish’s ability to give up. As the bass files that it isn’t getting everywhere, it swims harder, and astroglia exercise ramps up. When astroglia exercise reaches a threshold, the cells send a neuronal signal that the fish should prevent swimming.

The latest research shows that an overstimulating astroglia result in a long-lasting destruction of the “giving up” actions. This overstimulation, which occurs through ketamine’s activation of noradrenergic neurons that install astrocytes, appears to immediately reduce the astroglia stand’s sensitivity, causing the fish to maintain swimming generally, even when it isn’t getting anywhere.

Alex Chen, a joint PhD student in the Ahrens Lab at Janelia and the Engert Lab at Harvard, is a co-lead author on the paper.” Our paper suggests that these astroglia, this non-neuronal cell population, are playing a very important role, and some of the key effects of these antidepressant compounds go through changes in astroglial physiology,” he says.

The team’s findings, which also reveal that astrocytes are similarly activated in mice, could aid in better understanding how antidepressants function in the brain, which might lead to the development of safer and more potent treatments for depression.

Scientists have spent decades trying to understand how antidepressants work on a molecular level, with much of their research focusing on the drugs ‘ effects on neurons.

According to Marc Duque Ramez, a PhD student in the Engert Lab and co-lead author on the paper,” I think our research suggests that targeting these astrocytes to find new treatments could be a fascinating way to go.”

Using zebrafish to test ketamine

The project began when Duque and Chen, the team’s leaders, were interested in experimenting with antidepressants that had previously been tested on rodents and had been tested on humans. Because zebrafish are small and translucent, researchers can image each animal’s entire brain to better track the drug’s effects.

The Ahrens Lab had shown in earlier work that zebrafish exhibit a trait known as futility-induced passivity, or “giving up” – a behavior that has also been seen in rodents. The researchers fixed the fish in place and displayed various visual patterns to them using a virtual reality setup.

They wiggled their tails as though they were moving forward when the fish saw a pattern that resembled a backward motion pattern. When the pattern changed to one simulating being stuck in place, the animals would struggle at first, then give up, become passive, and stop swimming.  ,

The researchers report that ketamine had a protective effect on this giving up behavior for more than a day in the new study. The fish still struggled when their swimming was poor, but they did not give up as easily and were less reticent.

The authors also tested other fast-acting antidepressants, such as psychedelic compounds, and found a reduction in passivity like they saw with ketamine. On the other hand, stress-inducing treatments, such as chronic glucocorticoids, increased the giving up behavior.

Imaging reveals action on astroglia

Next, the team turned their attention to what the drug was doing in the fish’s brain. The Ahrens Lab’s earlier research revealed that a particular glial cell called radial astrocytes is responsible for the giving up action.

ketamine increased the amount of calcium at the astrocytes, according to whole-brain imaging, demonstrating that the drug continued to activate these cells for many minutes after administration.

The researchers believe that although short or quick increases in astroglia calcium may cause behavior to change, the aftereffects of the ketamine-induced flood of calcium lower the astroglia’s response to the futility signal that causes behavior, making the fish more robust in these behavioral situations, or less likely to give up, in the future.

” It’s desensitized because during ketamine it was so hyperactivated”, says Janelia Senior Group Leader Misha Ahrens, a senior author on the paper. ” It’s like taking a cold shower; afterwards, you’re a little less sensitivity to the cold, but on a cellular and molecular level.”

Additionally, the researchers discovered that mammals were able to operate this same mechanism. Eric Hsu, a graduate student at Johns Hopkins and co-lead author on the paper, discovered that astrocytes are similarly activated in mice both when they exhibit “giving up” behavior and when they are exposed to ketamine.  ,

Dwight Bergles, a senior author on the paper and a professor of neuroscience at Johns Hopkins, says that” this evidence of cross-species conservation increases the likelihood that comparable mechanisms exist in humans.”

Although how ketamine works on astrocytes and how that affects neuronal and astroglia physiology is still unknown, the team’s study demonstrates that it raises norepinephrine levels. However, the findings do suggest that astroglia might play a role in depression and could inform future research.

This might serve as a model for pieces of the mammalian brain, according to Ahrens, but we need to be cautious when taking these results too literally.  ,

About this news from neuropharmacology research

Author: Nanci Bompey

Source: HHMI

Contact: Nanci Bompey – HHMI

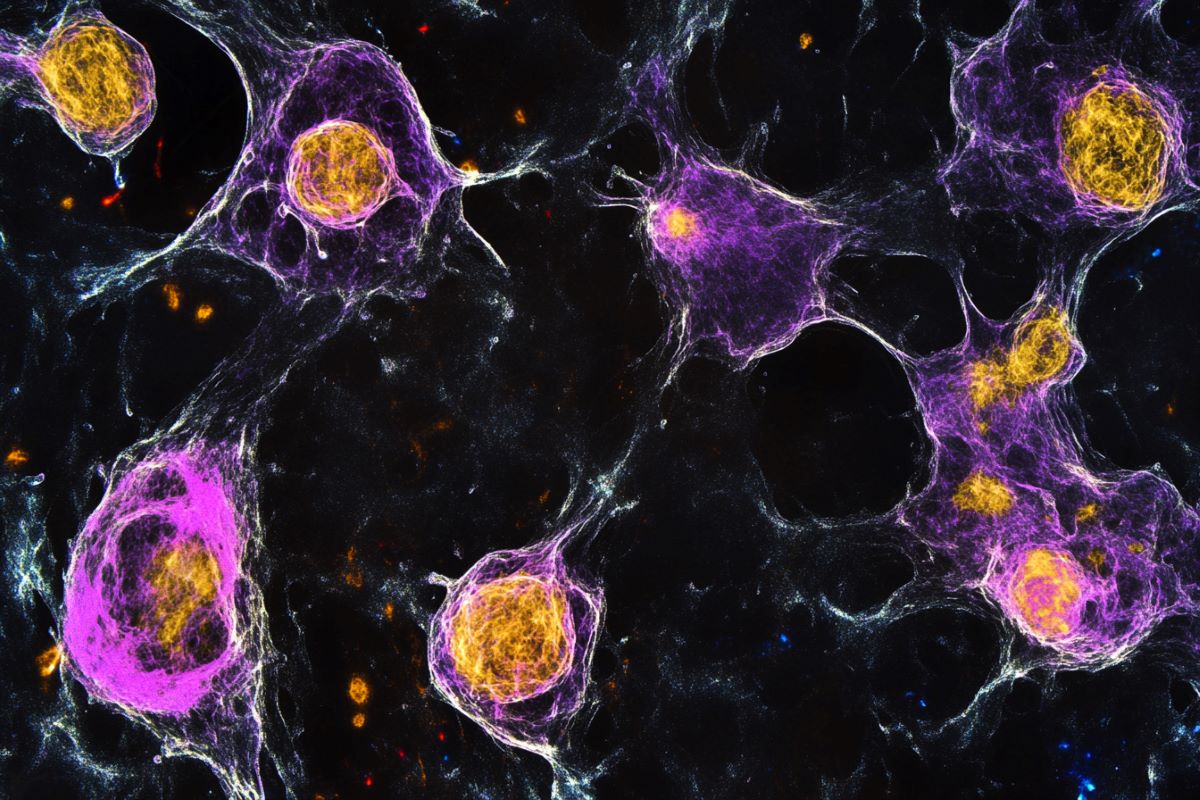

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Open access.

” Ketamine induces plasticity in a norepinephrine-astroglial circuit to promote behavioral perseverance” by Alex Chen et al. Neuron

Abstract

Ketamine induces plasticity in a norepinephrine-astroglial circuit to promote behavioral perseverance

KEMA can cause long-lasting behavioral and mood changes. We found that brief ketamine exposure causes long-term suppression of futility-induced passivity in larval zebrafish, reversing the “giving-up” response that normally occurs when swimming fails to cause forward movement.

Whole-brain imaging revealed that ketamine hyperactivates the norepinephrine-astroglia circuit responsible for passivity. After ketamine washout, this circuit exhibits hyposensitivity to futility, leading to long-term increased perseverance.

Pharmacological, chemogenetic, and optogenetic manipulations show that norepinephrine and astrocytes are necessary and sufficient for ketamine’s long-term perseverance-enhancing aftereffects. In addition, in-vivo and in-vivo calcium imaging revealed that astrocytes in adult mouse cortex are similarly activated during futility in the tail suspension test and that acute ketamine exposure also leads to astrocyte hyperactivation.

The identification of novel approaches to treating affective disorders may be influenced by evidence that plasticity in this pathway can alter the behavioral response to futility and the conservation of ketamine’s modulation of noradrenergic-astroglial circuits across species.