Summary: Scientists have discovered that adult hormones like estrogen and progesterone may trigger immune cell near the spinal cord to release normal drugs, easing problems before it reaches the head. These immune cells, known as T regulatory cells (T-regs ), are located in the meninges and produce the painkilling molecule enkephalin in response to hormonal signals.

The result appears certain to females, offering information into why some soreness treatments work better for women and why older women may experience more severe pain. This just uncovered system could lead to sex-specific treatments and innovative solutions for the millions affected by severe pain.

Important Facts:

- Hormone-Driven Relief: Estrogen and progesterone fast T-regs to release natural drugs.

- Sex-Specific Answer: Adult animals without T-regs became more pain-sensitive, men did not.

- Medical Possible: Built T-regs may provide a new method for chronic pain relief.

Origin: UCSF

Scientists have discovered a novel system that works via an defense body and points toward a different way of treating chronic pain.  ,

Female hormones may reduce problems by making immune cell near the nerve wire produce opioids, a new research from experts at UC San Francisco has found. This stops problems signs before they get to the head.  ,

The finding may assist with developing innovative treatments for chronic pain. It may also reveal why some medications work better for women than men and why older people experience more problems.  ,

The work reveals an entirely new role for T regulatory immune cells (T-regs ), which are known for their ability to reduce inflammation.  ,

” The fact that there’s a sex-dependent effect on these cell – driven by estrogen and progesterone – and that it’s no related at all to any immune function is pretty unusual”, said Elora Midavaine, PhD, a doctoral brother. She is the first author of the study, which was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

It appears April 4 in , Science.  ,

The scientists looked at T-regs in the protective layers that encase the brain and spinal cord in animals. Until then, experts thought these cells, called the pericardium, only served to safeguard the central nervous system and reduce waste. T-regs were just discovered that in recent years.  ,

” What we are showing now is that the immune system actually uses the pericardium to connect with distant cells that detect experience on the body”, said , Sakeen Kashem, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of cardiology.

” This is something we hadn’t known before”.  ,

That communication begins when a neuron, often near the skin, senses something that could cause pain. The neuron then sends a signal to the spinal cord.  ,

The team found that the meninges surrounding the lower part of the spinal cord harbor an abundance of T-regs. To learn what their function was, the researchers knocked the cells out with a toxin.  ,

The effect was striking: Without the T-regs, female mice became more sensitive to pain, while male mice did not. This sex-specific difference suggested that female mice rely more on T-regs to manage pain.  ,

” It was both fascinating and puzzling”, said Kashem, who co-led the study with Allan Basbaum, PhD. ” It actually made me skeptical initially” . ,

Further experiments revealed a relationship between T-regs and female hormones that no one had seen before: Estrogen and progesterone were prompting the cells to churn out painkilling enkephalin.  ,

Exactly how the hormones do this is a question the team hopes to answer in a future study. But even without that understanding, the awareness of this sex-dependent pathway is likely to lead to much-needed new approaches for treating pain.  ,

In the short run, it may help physicians choose medications that could be more effective for a patient, depending on their sex. Certain migraine treatments, for example, are known to work better on women than men.  ,

This could be particularly helpful for women who have gone through menopause and no longer produce estrogen and progesterone, many of whom experience chronic pain.  ,

The researchers have begun looking into the possibility of engineering T-regs to produce enkephalin on a constant basis in both men and women.  ,

” If that approach is successful, it could really change the lives of the nearly 20 % of Americans who experience chronic pain that is not adequately treated”, Basbaum said.  ,

Authors: Other authors on the study include Beatriz Moraes, Jorge Benitez, Sian Rodriguez, Joao Braz, Nathan Kochhar and Walter Eckalbar of UCSF, Lin Tian of the Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience, Ana Domingos of University of Oxford and John E. Pintar of Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

Funding:  , This study is funded in part by National Institutes of Health grants ( T32AR007175-44, NSR35NS097306 ). For other funders, please see the study.  ,

About this pain research news

Author: Robin Marks

Source: UCSF

Contact: Robin Marks – UCSF

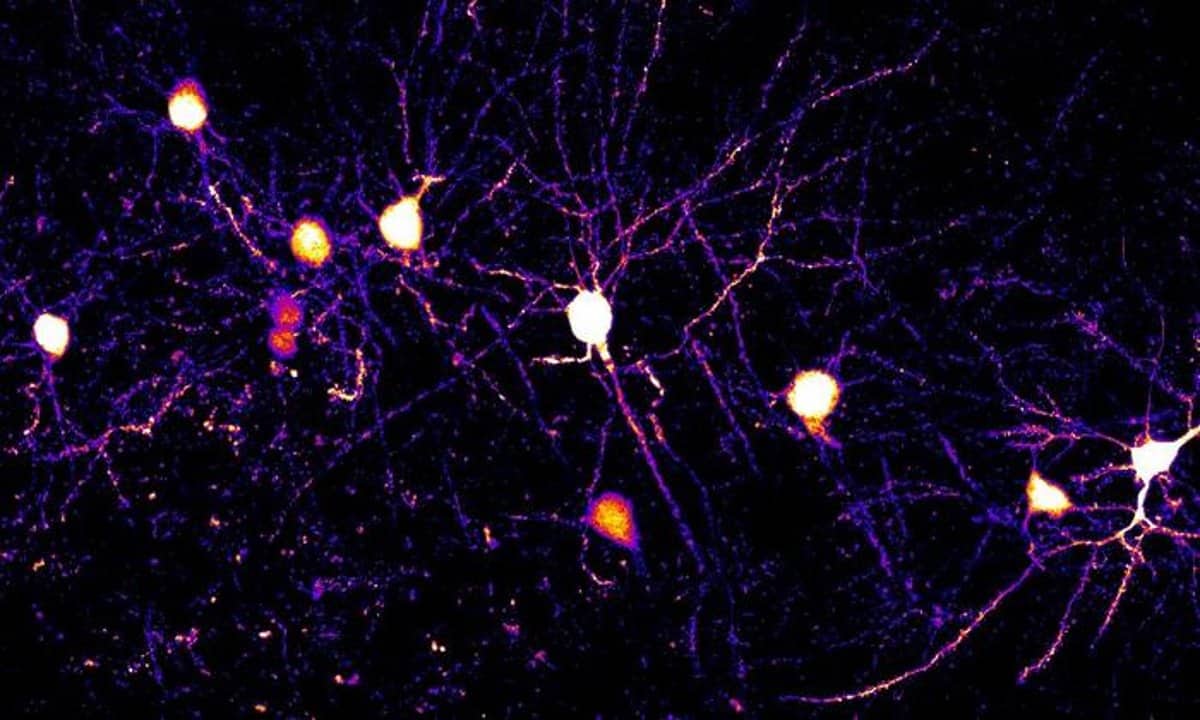

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Original Research: Closed access.

” Meningeal regulatory T cells inhibit nociception in female mice” by Elora Midavaine et al. Science

Abstract

Meningeal regulatory T cells inhibit nociception in female mice

T cells have emerged as orchestrators of pain amplification, but the mechanism by which T cells control pain processing is unresolved.

We found that regulatory T cells ( Treg , cells ) could inhibit nociception through a mechanism that was not dependent on their ability to regulate immune activation and tissue repair.

Site-specific depletion or expansion of meningeal Treg , cells (mTreg , cells ) in mice led to female-specific and sex hormone–dependent modulation of mechanical sensitivity.

Specifically, mTreg , cells produced the endogenous opioid enkephalin that exerted an antinociceptive action through the delta opioid receptor expressed by MrgprD+ , sensory neurons.

Although enkephalin restrains nociceptive processing, it was dispensable for Treg , cell–mediated immunosuppression.

Thus, our findings uncovered a sexually dimorphic immunological circuit that restrains nociception, establishing Treg , cells as sentinels of pain homeostasis.