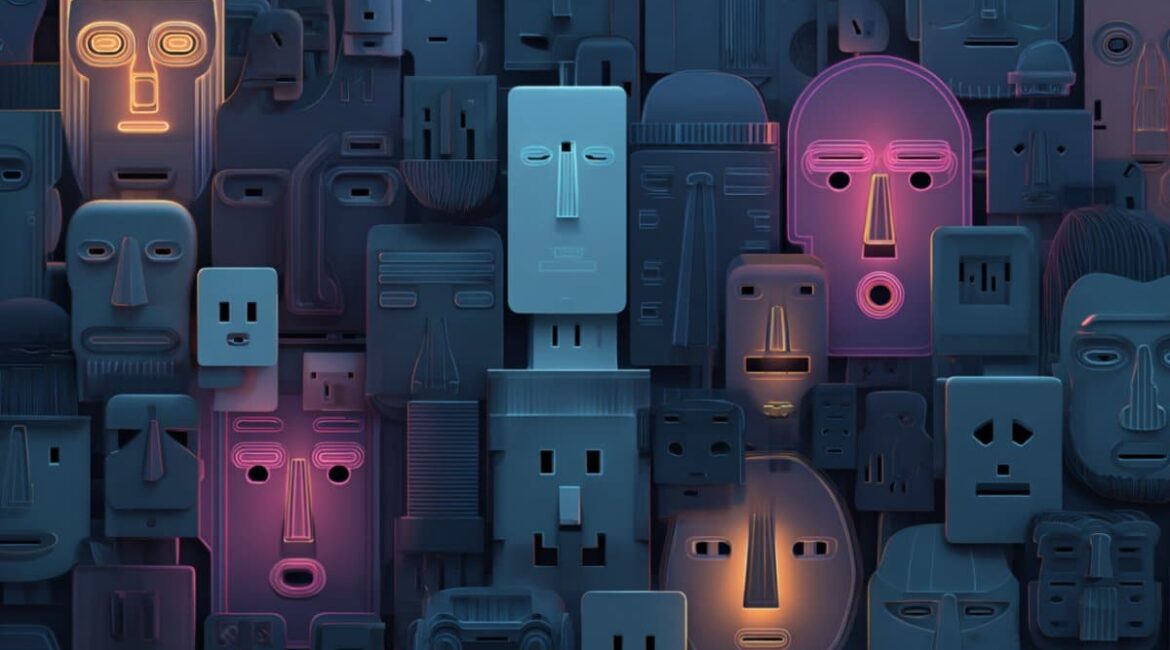

a new review notes that seeing faces in objects—known as experience pareidolia—engenders a potent effortful reply. Experts compared how people react to imagined faces and real-life averted glances, finding that both bring attention through various methods.

While true people use certain cues like eye direction to control our perceptions, pareidolia activates a wider, more integrated attention pattern. This more powerful answer to simulated eyes may have use in advertising and design.

Important Information

- Pareidolia Power: Face-like objects attract viewers ‘ attention more than averted glances in real life.

- Various Mechanisms: Pareidolia uses total structure, while real faces are focused on particular characteristics.

- Marketing Potential: Product promotion does use face-like designs to increase consumer interest.

University of Surrey Cause

You might have encountered the sensation of face pareidolia if you have ever seen faces or expressions that resemble humans in common objects.

A new study from the University of Surrey has examined how this trend captures our focus, which could be used by advertisers to promote upcoming products.  ,

The study, which was published in , i-Perception, examined the distinctions between our attention being focused on something when a area turns away from another subject’s eyes or face – and when it is focused on pareidolia, imagined face-like objects.  ,  ,

The researchers used 54 participants in four “gaze cueing work” experiments to examine how our attention is impacted by another person’s gaze’s direction.

Participants constantly shifted their attention, according to the study’s findings, when alleviated gazes and pareidolia appear.  ,

The methods underpinning the focus on this subject are, however, very different. We are generally drawn to the eye area of averted gazes, but we are also drawn to pareidolia’s systematic framework of their “faces,” which gave us a more focused and focused response.  ,

Dr. Di Fu, a teacher in cognitive science at the University of Surrey, said:”  ,

Our research shows that both solved gazes from perceived and real faces can guide our gaze, but they do so by using various pathways. We process true faces by paying attention to particular characteristics, such as the eye’s direction.

However, with face-like objects, we consider their entire architecture and the location of their “eye-like features,” which gives rise to a stronger interest response. ”  ,

The conclusions of the research may have repercussions that go beyond understanding how our brains process data. Dr. Fu continues:

Our conclusions may also have useful applications, particularly in areas like product marketing. Advertising could possibly include face-like arrangements with notable eye-like elements into their designs, attracting more attention from consumers and making their products memorable. ”  ,

About this information about pareidolia and sensory perception.

Author: Melanie Battolla

Source: University of Surrey

Contact: Melanie Battolla – University of Surrey

Image: The image is credited to Neuroscience News

Start access to original research.

By Di Fu and albert.,” How face-like items and averted stare faces orient our interest” i-Perception

Abstract

How do face-like materials and averted gaze-oriented objects orient our focus?

People interpret minimal heads from face-like objects, or” face prosopagnosia,” in real life. Similar to alleviated glances, face-like objects can captivate the viewer’s attention.

The similarities and differences in effortful swings caused by these two different types of stimulation are still unexplored.

This research compares the cueing results of face-like items and averted stare faces, revealing both commonalities and different underlying mechanisms through a stare cueing task.

Our findings demonstrate that while both stimuli may cause effortful shifts, their mechanisms differ: face-like objects use their global layout to increase attentional shifts by triggering eye-like features while solved eye faces rely on processing native features like gaze direction.

These findings help us better understand the digesting mechanisms that control how the brain represents physical characteristics even when there are no actual visual stimuli.

This study provides a solid conceptual basis for future research into how face-like stimulation can be used to improve human understanding and focus.